Presenting a post-war alternative to the musical genre, the first film to showcase rock music was Rock Around The Clock (1956). Where previous musicals were produced for mass audiences, Rock Around The Clock catered to a niche audience of teens and young adults. Where Busby Berkley’s musicals had presented lavish sets and stage productions that bordered on the surreal, Rock Around The Clock offered modest dance numbers showcasing the current craze. What sets Rock Around The Clock apart from its musical predecessors is that the people involved with the film seem to have little or no previous musical experience. The producer, Sam Katzman, had made a career out of budget exploitation films catering to a younger audience, while director Fred F. Sears and writer Robert E. Kent had previously worked on budget crime or adventure films. Neither producer, director nor writer seem to have had any experience working in the musical genre, yet all were to help establish a new trend in the way rock would inform the musical style. One need only watch a musicals like West Side Story (1961), Bye Bye Birdie (1963), Grease (1978) or even John Water’s Hairspray (1988) to see how Rock Around The Clock or the sequel Don’t Knock The Rock (1956) influenced post-rock musicals. The music of Rock Around The Clock is a mixture of early do wop, Latin jazz, rock and swing, with acts such as Bill Haley and the Comets, The Platters and Tony Martinez, performing on a modest stage.

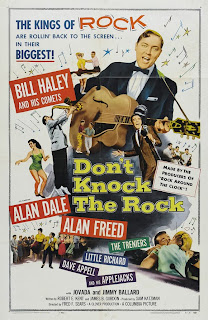

Don’t Knock The Rock follows a similar pattern to its predecessor, presenting a well-mannered singer and rock band to a small town, inhabited by musically narrow-minded folks. Interestingly, the film presents unthreatening musicians who get blamed for youth delinquency, as if they were characters from Blackboard Jungle (1955). Yet the film really doesn’t share as much with the delinquency genre as it would like one to think; it focuses more on the prejudices of a small town mentality rather than the rebellions of a teenaged delinquent. Although the chain-smoking, sweet-talking, Bobby Darin-ish crooner Alan Dale, is considered to be a threat to this small town, he is in actuality harmless. However, his character is not unlike many musical genre leads, which isn’t necessarily emblematic of the juvenile films. He lifts his eyebrows, releases a deep voice and sings at any opportunity, as the film meshes an old genre archetype with a modern perspective. Bill Haley and the Comets come off as extremely polite as well, though little acting is required of them. Little Richard performs a couple of songs, but considering he is an African-American in 1956, he is given zero screen-time outside of these moments. Placed in an unthreatening framework of a low budget social drama, both Sam Katzman films offer an introduction to a new sound and style. This rock film identity would be further developed in Elvis Presely’s third vehicle Jailhouse Rock (1957).

If earlier films introduced societal fears of the rebel rock and roller, then Elvis Presley’s Vince Everett in Jailhouse Rock delivers the goods. Not only is he a good-looking performer, but he’s a non-conformist as well. Elvis’ Vince is an unpredictable, egotistical live wire, who just might break a guitar for your attention, or beat you to death if he is threatened. This is the kind of character that the town’s folk fears, yet he has all the attributes for teen appeal. Vince, who mumbles, is at times inarticulate and reactionary like James Dean in Rebel Without A Cause (1955). As the generation was ushering in misfits like Dean, so was the musical genre. Elvis was the new face of rock, yet his type of character was already beginning to appear in the 50s musical with the casting of Marlon Brando in Guys and Dolls (1955). Elvis seemed to epitomize the new rebel as a character in film and in real life; in fact, during his live performances, TV stations censored his moves from the waist down. Whether the musical genre was changing on its own or through popular music, surely rock tipped it over as a new commodity that film companies could mine. At the end of the film, the audience is treated to a musical type performance from Elvis with his song “Jailhouse Rock,” which includes a jail cell façade with cellmate dancers. Although this performance initially appears to mimic older musical numbers, it is revealed to be part of a television station recording, modernizing the musical genre with an acknowledgement of television. This evolution of television incorporated with rock music is parallel to the film Singin’ In The Rain (1952), which documents the evolution of sound film. These rock and television elements would also be further mimicked in Bye By Birdie, showcasing Conrad Birdie acts as an Elvis imitation.

The Girl Can’t Help It (1956) presents a different introduction to rock music mixing the classic musical approach with screwball comedy. Where the previous three films were shot on a miniscule budget in black and white, The Girl Can’t Help It offers widescreen and beautiful color in its presentation. Keeping within the spirit of the old musical mold, the film brings to life performances of Little Richard, Gene Vincent, Fats Domino, The Platters (they sure got around) and others. Yet all of these bands are shown through the exposure of television or the jukebox. In some ways, The Girl Can’t Help It is the most modernist in approach with its flaunting of every technological advancement in music and film at that time. Strangely the film is wrapped in a screwball comedic love triangle, which is also similar to the earlier musicals. The gorgeous Jayne Mansfield makes for a perfect rock suggestive sex symbol, though Tom Ewell and Edmond O’Brien do not. The casting of these two older actors are about the furthest one can get from the iconic cool of Elvis Presley. Funny as they may be, watching Tom Ewell snag both Marilyn Monroe and Jayne Mansfield (in fantasy or reality) is just upsetting. If the other three films struggled to present a disenfranchised or misunderstood youth, The Girl Can’t Help It makes none such pretenses and probably suffers from “squaresville” because of it.

As the post-war ideologies shifted in the 50s, so did music and cinematic styles. If the rock film was a threat to the classic musical structure, it did a pretty good job eliminating it by the late 60s with concert films like Woodstock (1970). However, in this early period of the 50s, these rock films acted as a new wave of cinema, rethinking the musical mold with a fresh perspective and contributing to its evolution.

No comments:

Post a Comment